The following comes from Yahoo Sports:

Who knows what made Michael DeMocker pick up a camera at that one instant on the night they reopened the Superdome. He's a photographer, a man trained not to question inner voices after two decades of documenting football and crime. As a rule he never takes pictures of punts, but it was the first drive of the first game on a night flush with euphoria. Nothing made much sense.

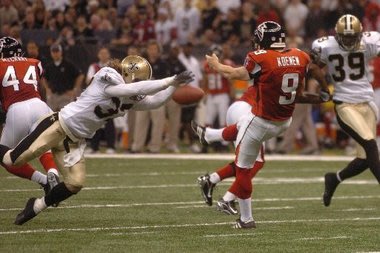

And so just after 7:30 p.m. on Sept. 25, 2006, with the most visible symbol of Hurricane Katrina's wrath repaired, DeMocker stopped just short of the Atlanta Falcons' 10-yard line. He clutched his The Times-Picayune-issued camera, focused on Falcons punter Michael Koenen and pushed the shutter button. As Koenen began to punt, DeMocker caught a glimpse of a white New Orleans Saints jersey streaking through the frame. There was a noise. A scramble. A blocked punt! Then a tumble in the end zone. Touchdown! And a roar like nothing anyone heard in the Superdome before or since crashed down all around.

DeMocker looked down at his camera, flipped through his shots and saw clearly the perfect image of Saints safety Steve Gleason flying through the air, hands on the ball right after it left Koenen's foot. DeMocker's heart raced. He had the shot! He had been in the dome in those first few days after Katrina, standing on this very field then with its turf ruined, seats waterlogged and that great gaping hole in the ceiling. He thought that day they should just rip it down. Instead they rebuilt it. And now this? A blocked punt and a touchdown? Just seconds into the game?

He reached into his camera and pulled out the disc. Only then did he realize he was sobbing.

Years later the Saints would hand DeMocker's picture to a sculptor who would cast a giant metal image of Gleason blocking Koenen's punt. They would put it in front of the Superdome. And beneath the statue would rest a stand with a single word: "Rebirth." That's the only thing it could possibly say. For many here, the instant Gleason blocked the punt was when they knew New Orleans would be fine.

Ask nearly anyone from the city who picked through the ruins of a flooded house to name their favorite sports moment and they will mention the Super Bowl the Saints finally won in 2010 over the Colts or the field goal two weeks before that sent them to the game. But invariably those will be beautiful but secondary – dreams they never imagined. The first, they almost always say, came when Gleason blocked the punt.

"Gleason's play transcends football," says Christopher Bravender, a lifelong Saints fan. "Our city was crippled. We needed the Saints and we needed them desperately. We needed the distraction. We needed the inspiration. We needed to feel like we were part of something. That blocked punt literally helped people rebuild their homes. It symbolized being back.

"I get chills just thinking about it. He lifted a fallen city and I can say with no hesitation that he made the biggest play in Saints history."

Then there too is the fact it was Gleason who blocked the punt. There couldn't have been anyone more perfect. His father-in-law, Paul Varisco, says this. Varisco is a local musician of note, the leader of a once popular band called Paul Varisco & The Milestones. It is a detail that is important to people in New Orleans, just as its important that Gleason – who came from Washington State – married a local woman and lived in the city's borders. He wanted to be one of them.

He was not an extremely gifted player. His greatest contribution to the Saints was that he was a relentless special teams player who made blocking punts something of a specialty. He had long hair, loved local music and rode a bicycle around town. In a sense, he was not like an athlete, but rather like everyone else.

"He's humble and he didn't like the spotlight, he didn't go seeking the media," Varisco says. "I don't think he was prepared for being a celebrity. He's not one to beat his chest."

Yet just like this city where triumph too regularly meets heartbreak, Gleason was diagnosed with ALS three years ago. The man who flew through DeMocker's camera lens cannot walk. He struggles to speak. This Super Bowl week is not about the blocked punt for him, but rather his foundation,TeamGleason.org, and the push to find a cure for the disease that slowly takes little pieces of the life he once had.

And somehow the disease has made Gleason's block even more significant. It's almost as if much of New Orleans aches for every bit of the improbable hero that slips away from them. For he is the one they will never forget.

Something was growing that day the dome re-opened. It built through a morning suffused with anticipation. It broiled in the afternoon sun. The dome had been rebuilt in nine months, which had seemed impossible. Everyone wanted to celebrate. People walked out of work, they filled the bars of the French Quarter and surged over Poydras Street, the main avenue that goes by the dome.

There was a power in the throng. Something bigger than anyone had seen. Never in the months after Katrina had everyone come back together like this. The mob closed Poydras then slowly surged toward the stadium. Inside they wept. The stadium dome smelled new. The building New Orleans had left behind with its hole in the roof and torn turf and ruined seats, shined. U2 and Green Day played an opening show, unveiling a song called "The Saints Are Coming." Across the field a line of local New Orleans musicians backed them in a blast of brass.

A roar climbed to the roof, rattling through the girders and bouncing to the field. It boomed through the kickoff and reached a deafening pitch when Falcons quarterback Michael Vick dropped the ball before falling on it. Then Atlanta lined up to punt. Koenen stood just inside his 20. The snap came. The roar so loud now. He caught the ball, swung his leg. Gleason flew in …

Thunk.

Then mayhem.

In the stands, a lifelong Saints fan named Ralph Avila threw his hands in the air while still holding a drink. It went flying on the people in front of him. He looked down and saw somebody's nachos sprawled on the concrete.

The father of a Saints fan, Nathaniel Rogers, felt something go in his ears. To this day, he still has hearing loss.

Bravender stood at his seat and "cried like I had just met a family member I was sure had died in the storm."

On the sidelines, Quint Davis, the producer of New Orleans Jazz Fest, grabbed the shirt of famed Grammy producer Ken Ehrlich – with whom he had put together the pregame show – and ripped off Ehrlich's buttons.

And in a room beneath the stands, the members of U2, who had just played the pregame show, heard a rumble above and stared at the TV screen, their faces filled with wonder.

"It was just a huge release of emotion," says Chris Webre, a longtime Saints fan who was at the game. "It was excitement and tears. It was just a huge emotional release. From Aug. 29, 2005 [the day of Katrina] up to that day all we heard was 'New Orleans shouldn't be rebuilt.' 'The dome shouldn't be rebuilt.' 'The Saints shouldn't return to New Orleans.' All we heard was negativity.

"This was positive."

Down on the field, DeMocker tucked the photo disc in an envelope that photographers hand to runners. The runner would take the envelope to a Times-Picayune photo editor who was in a room beneath the stands. He knew he had something big.

"I couldn't believe it," DeMocker says. "I didn't think I had it at first. I really didn't see the block as I was shooting."

He was amazed at his fortune. His first instinct had been to walk down the sideline and around the back to the end zone. Since the Saints would be getting the ball in good position following the punt, he thought he might be in position to get some shots of them driving toward him. He still doesn't know why he stopped near the 10.

But the thing that stunned him the most was the detail he had managed to capture – the blur of the ball hitting Gleason's hands at the moment of impact. He had Gleason's feet off the ground. The player's golden hair was flowing from under his helmet. Today cameras work so much faster. The shutter can open and shut so many more times on an automatic drive. The chances now of getting the ball on Gleason's hands are far larger than they were then. It struck DeMocker just how fortunate he was.

Before giving the envelope to the runner, DeMocker drew 10 stars around a note that mentioned Gleason's punt. He laughed as he thought it looked like the margins of a little girl's notebook. All that he was missing, he said to himself, were drawings of unicorns. It was that important, though. The editors had to see his picture. They too, he knew, would be amazed.

"I got the shot!" he yelled to the runner. "I got the shot!"

The runner disappeared. DeMocker turned back to the game.

The Saints not only won that night, they tore apart the Falcons. The final score was 23-3. Perhaps more significant was the fact they were 3-0. Given the team had won just three games the year before as they bounced between San Antonio and Baton Rouge, this was no small accomplishment. Added to the fact they had beaten their hated rivals and Vick was awful in the game, a sense began to settle in that maybe things were indeed different in New Orleans.

Perhaps after a year of hell, they were all going to survive after all.

"That night was so important," says New Orleans resident Patty Glaser, who was at the game with her family. "It was one of the most powerful symbols in the rebuilding after Katrina. Everyone was asking: 'Is the dome re-opening?' Having the dome open and winning that game was the thing that told us we cold do it too. We could rebuild our homes."

DeMocker laughs.

After the game he raced back to The Times-Picayune offices to return his equipment and see where they ran his photo of the Gleason blocked punt. He picked up the first edition of the paper and scanned it. Nothing. No picture.

He asked, none too quietly, "what happened?"

Really, he had the Gleason block?, they asked. No one had seen it. Somehow, in the mayhem they missed it. Computers were opened, files scanned. Eventually, yes, someone found it. There it was. Gleason, his hands outstretched, the ball about to strike his palms. It made the paper's second edition.

It is the only photograph DeMocker keeps in his New Orleans home. It sits on the mantel above his fireplace. His wife will allow no other sports or crime pictures, he says. This one is an exception in part because it is next to a picture of he and his wife meeting Gleason. But also something more, something bigger. For the picture just seems to scream: New Orleans is back.

"If you were in the city after Katrina it was like that scene in the movie where the hero gets pummeled and pummeled by the bully," DeMocker says. "Then just when the hero is about to succumb, he throws a punch into the belly of the bully."

He pauses.

"It was like a big [expletive] you to Katrina," he says.

Which is more than a photograph could ever say.